Simply put: the canonical perspective is the conviction that one part of Scripture is best understood for the role it plays in the whole.

In the past 150 years, there have been numerous scholarly, “critical” schools with various visions defining an accurate methodology for interpreting Scripture. To cover the most important: historical criticism focused on interpreting Scripture as an artifact of ancient history. Source criticism looked for the sources that are allegedly beneath the texts themselves. Form criticism tried to understand how any given section of Scripture related to universal literary genres. Redaction criticism investigated how the authors and editors of texts seamed together their sources into composite texts. Literary criticism brings ancient texts into conversation with other texts to let their literary features stand out. Social criticism reads what each text implies about the social group from which the text came. If this sounds a bit speculative, confusing, and somewhat wrong-headed to you, you’re not alone!

The Biblical scholar Brevard Childs thought so too. Childs felt like all this effort had kept Biblical scholars from understanding the text itself. While not necessarily denying some helpful insights from any of these schools, Childs developed a new/old type of interpretation which goes by various names, but which I will call the Canonical Perspective. Childs’ modern followers include Christopher Seitz, Mark Gignilliat, Don Collett, and Michael Kruger to name a few.

I have some criticisms of Childs,1 nevertheless, I think the Canonical Perspective is helpful for the following reasons:

A Focus on the text itself2 - You will notice that many of the various “critical schools” are trying to get behind the text in one way or another. Historical criticism tries to get to historical context, source criticism into the sources behind the text (which are usually dubious at best), redaction criticism into the mind of the redactor, etc.. However, the canonical perspective emphasizes the text itself in the form we have it.

A Focus on Scripture as a text of faith - The Canonical Perspective recognizes that texts were written from the perspective of faith. They were written by believers for believers. They have genres such as poetry, narrative, and prose. But fundamentally, the texts are important because they use genre as a vehicle for religious purposes. They were understood to be normative and authoritative. You cannot understand the texts apart from the perspective of the authors and readers of the text, namely, from faith.

A Belief in Typology - From the start, Childs recognized the necessity of typology and figure for the unified story of Scriptures. They recognize that characters in Scripture fit together like Russian-nesting dolls, and that the Old and New Testaments are unified by employing types, obviously culminating in Christ.

Scripture as a Collection of Collections - Sometimes Scripture is called a “collection of authoritative books.” That is a true but under-stated fact; it is more accurate to say Scripture is a “collection of collections.” The Old Testament has three major collections: the Law,3 the Prophets,4 and the Writings5 (Luke 24:44). Some (myself included) think the New Testament mirrors this order. How a book fits into one of these collections matters for how we understand it. More on that below.

Covenant - Canon and covenant are integrally connected. As Meredith Kline has convincingly argued,6 God’s covenant with humans demands a written code (Torah). This is expanded through the prophets, and defended in the “writings.”7 This also intuitively connects how we understand the New Testament writings as the code of the new covenant. It also implies that Biblical theology should be covenant theology; after all, if canon is tied up so tightly with covenant, how could we understand Biblical theology apart from covenant?

An emphasis on Church history - The Canonical Perspective gives great purchase to the idea that texts are received by communities of faith. This means that it is important to understand both how John Calvin and Jonathan Edwards read the Bible. The Canonical Perspective implies that the history of Biblical interpretation matters.

Let me give an example of the canonical perspective:

Consider Ruth. Typically, when we interpret Ruth, we see it as the prelude to the David epic in 1–2 Samuel where it rests in the English Bible. This is because of the important genealogy of King David in Ruth 4. It probably would surprise most moderns to know, however, that Ruth is usually placed not alongside 1–2 Samuel but Psalms, Proverbs, and Job in the Hebrew Bible. Consider the first chapter of Ruth: the family goes into a famine-induced exile, Mahlon, Chilion, and Elimelech die. Naomi is abandoned by one of her daughters-in-law. She returns home with her other, indebted and having nothing—not even access to the family estate. In other words, much of the opening part of the book is about Naomi’s loss and suffering. The book’s main plot is how she and Ruth are redeemed.

Now, let me ask, when we read this book alongside Job, what emerges? How are they similar? Different? It seems to me that both books start with calamity and deal with the problem of suffering. They also end in restoration. They also involve redeemers and redemption. What does this imply for all who trust in God in suffering? However, the way they get there, the solutions to suffering, the way God interacts with his people are different. They are complementary (not contradictory). They help us understand the ways of God with suffering man. If we remove Ruth from the “Writings,” where it belongs in the Hebrew Bible, we might miss this connection. However, when we see Ruth as a book about wisdom and suffering, it comes into much clearer focus.

This is the value of a canonical perspective. I have found that the canonical perspective yields these kinds of insight over and over again. It is, simply put, a most rewarding ways to read Scripture.

He rejected Scripture’s self-authentication and gave little attention to ‘authorial intent,’ for example.

The scholarly terminology is typically “final form."

Genesis-Deuteronomy

Joshua, Judges, 1–2 Samuel, 1–2 Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the 12 Minor Prophets.

Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Solomon, Ruth, Esther, Ezra, Nehemiah, Daniel, Lamentations, 1–2 Chronicles.

Meredith Kline, The Structure of Biblical Authority (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 1997), 64–67.

Kline only applied this to the wisdom literature, but I think it can be applied to other books in the writings below.

I want to end this post with an invitation to two events put on by some friends of mine if you are in New England:

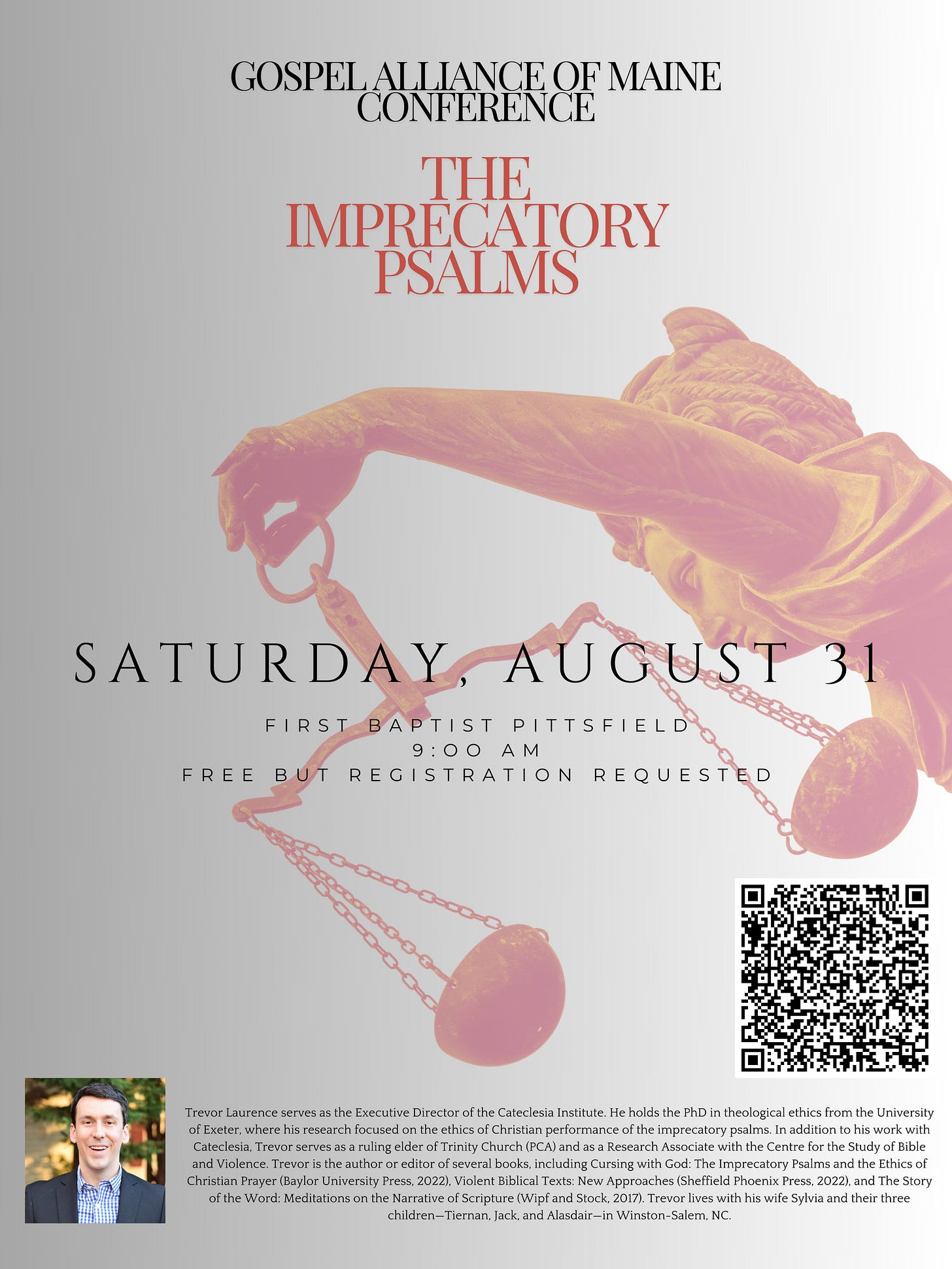

On August 31 at 9 AM, the Gospel Alliance of Maine is putting on a conference on the Imprecatory Psalms. The conference will be held at First Baptist Pittsfield.

On Saturday September 7, from 9 AM-2 PM, there will be a Men’s Conference at Windsor Christian Fellowship in Windsor, Maine. Register here.